Eritrea has deployed most of its army in Tigray region of Ethiopia. This is no secret. At minimum, 12 divisions have been fighting inside Tigray.

At first, the United States gave Eritrea a free pass, expressing “thanks to Eritrea for not being provoked” into retaliating after a TPLF rocket attack on Asmara. Later it admitted that Eritrea was a belligerent. The United Nations Secretary General repeated Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed’s assertion that Eritrean troops had not crossed the border. The Chairperson of the African Union has carefully said nothing on the issue.

It is lawful for a state to request the military assistance of another state. The involvement of Eritrea in Ethiopia isn’t illegal per se.

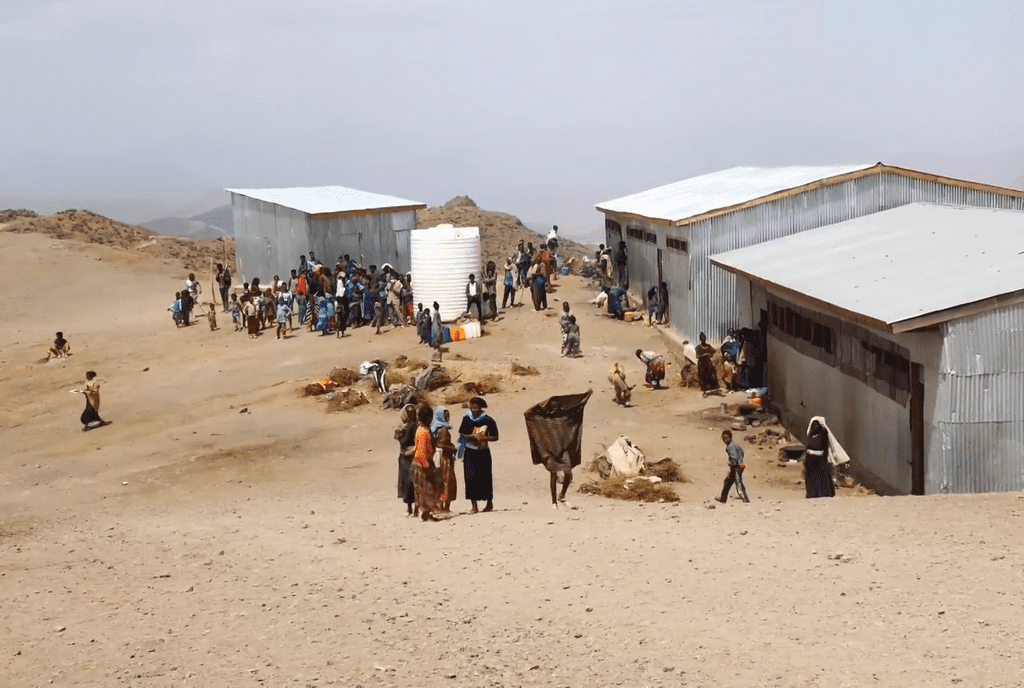

But there is mounting evidence that activities of Eritrean troops include perpetrating war crimes on a vast scale. Every report from the northern parts of Tigray speaks about Eritrean soldiers looting. They ransacked the town of Shire. They shelled Humera close to the Sudanese border. They systematically dismantled the university and pharmaceutical factory in Adigrat. They stole cars, generators, and high value goods. Now we hear that they are combing ordinary houses in towns and villages, taking such basic items as furniture, doors, and jerrycans. Eritreans are said to have emptied food stores and looted cattle, sheep and goats.

Catholic priests in Eritrea were horrified by the looted items coming into Eritrea from Tigray and admonished anyone buying them. Despite the information blackout, journalists have pieced together enough information on these actions.

International criminal law prohibits a belligerent from removing, destroying or rendering useless objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population. The fast-approaching humanitarian crisis with at least 2 million displaced is due not only to fighting but to starvation crimes such as these.

Eritrean troops overran and emptied four refugee camps where Eritreans who had escaped their country had been living, until last month under the protection of the Ethiopian government. That’s another violation of international law.

As the weeks pass, it is becoming ever clearer that President Isseyas Afewerki has long planned this war with the intention of annihilating the TPLF and reducing Tigray to a condition of complete incapacity. His strategy is to say nothing and make a fait accompli on the assumption that the world will, in due course, come to live with it.

If anyone should doubt Isseyas’s intent, they should reflect on the way in which he has dealt with domestic opposition. In September 2001, while international attention was consumed by the al-Qaeda attacks on New York and Washington DC, he arrested eleven high-ranking colleagues, heroes of the liberation war, who had called for democratization, and ten journalists. They have never been seen since. After PM Abiy Ahmed visited Asmara in 2018 to end the long-dormant peace process between the two countries, Eritrea did not liberalize or demobilize its army. Nothing was said about political prisoners. Eritreans complained that nothing changed for them. For Pres. Isseyas, it wasn’t peace—it was a new opportunity to consolidate despotism.

Who will call out Eritrea’s role in the destruction of Tigray?