We’re in World War X. It didn’t start last weekend, but it escalated. And the overnight ceasefire, even if it holds, didn’t de-escalate.

It’s not ‘World War Three’ because it’s not the next in sequence after World War Two—a world war doesn’t have to resemble 1914-1918 or 1939-1945. If we loosen our definition of ‘world war’ we can readily identify about seven ‘world wars’ in history, from the conquests of Chinggis Khan, through Tamerlane, the Spanish Empire at its height, and the Anglo-French wars of the 18th Century and the Napoleonic era, that haven’t been given numbers.

By one possible count we are in World War Ten—a first definition of World War X.

There’s another way of thinking about World War X, where the ‘X’ is a placeholder for a war that we don’t yet understand.

In the same way that virologists speak of ‘pathogen X’—the microbe they haven’t yet identified that will cause the next ‘pandemic X’—‘World War X’ is the war that we didn’t anticipate and haven’t yet figured out.

This is the first in a series of blog posts in which I will explore ‘World War X.’ I will look at the logics that are driving it, the stakes of the war, and what can be done to stop it.

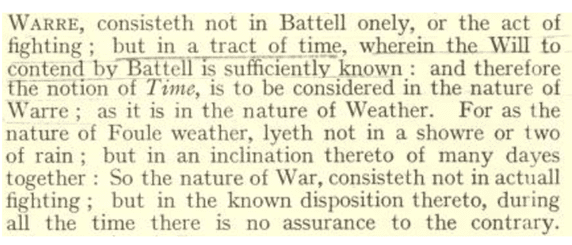

World War X is a fusion of different kinds of war, old and new. It has elements of Thomas Hobbes’s definition of ‘Warre’:

The Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz wrote that ‘every age has its own kind of war… and each period, therefore, needs its own theory of war.’ He defined war as the ‘conduct of politics by other means.’

World War X is an extension of contemporary politics. And as politics has changed, so has war.

Three characteristics of today’s politics are particularly relevant.

One is the return of wild power: disruptive power against established orders that are seen to have failed and to be beyond reform. It includes heroic violence: violence that legitimizes itself, that was a defining feature of pre-modern wars.

The counterpart of heroic violence is populist peacemaking.

The second is that power has become a tradable commodity, bought and sold according to rudimentary laws of the market. This was a feature of European worldwide wars of imperial expansion. In these political markets, a peace deal is a bargain—good for as long as market conditions hold.

The third is that the norms, institutions and practices that constrain the pursuit of power are collapsing. And with their disappearance, peace settlements as treaties or amended national constitutions are fading too. The United Nations system that was put in place to prevent the next world war after 1945 is, practically speaking, now irrelevant.

Today’s world political operating system is a fusion of money and power, kleptocracy and gangsterism. World War X is the fight to control this operating system, and win unlimited accumulation of power.

All weapons systems, all communications systems, all financial and economic tools, are weaponized to this end.

Let me elaborate my pre-emptive response to the main expected criticism.

Retired army officers who have become pundits, military historians, and others will respond that our current conflicts are nothing like total war as fought in the 20th century. They will say that there’s no direct military confrontation between today’s great powers, that no major economy is allocating anywhere near the huge proportion of output to the war effort that we saw in the 1940s, and that each one of the numerous armed conflicts and militarized inter-state encounters has its own specific, local causes—in short, that this is nothing like World Wars One or Two. And therefore, we can still avoid World War Three—if necessary by a pre-emptive military strike.

That’s my point: World War X is not like its 20th century predecessors.

Truth is, famously, the first casualty of war. Let me adapt this maxim to say that the first casualty of a world war is a candid discussion about it.

The United States military targeted Iran’s nuclear capacity with massive bombs. As collateral damage it blew up international law on the use of force. It also violated a much older honor code, which is respect for a good faith mediator. These will be much harder to rebuild.

World War Two and World War Three are evoked by the warriors of World War X.

They want to revisit the triumph of World War Two without having to fight it, to live the alternative history in which the rise of Hitler was stopped by a pre-emptive strike. They are discarding the hard-won lessons learned by those who actually fought that war. This is not taking us back to the pre-1945 era, it’s taking us back much further to a heroic era in which violence was its own legitimation.

It’s taking us to an era in which peace is a string of deals, for divine blessing, popular acclaim, and profit.

To adapt Hobbes, the defining feature of World War X is not the actual battle, but in ‘the known disposition thereto, during all the time there is no assurance to the contrary.’ In every country, at every turn, the readiness to use force first is increasing. The U.S. strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities didn’t start World War X, and nor did President Trump’s announcement of a ceasefire stop it. We had already crossed that river. What the strike did was to burn the boats that could have taken us back to a safer shore.