The Middle East is heading for a wider war. There’s a dangerous game of chicken with multiple actors. Each side refuses to listen to the moral story of the other.

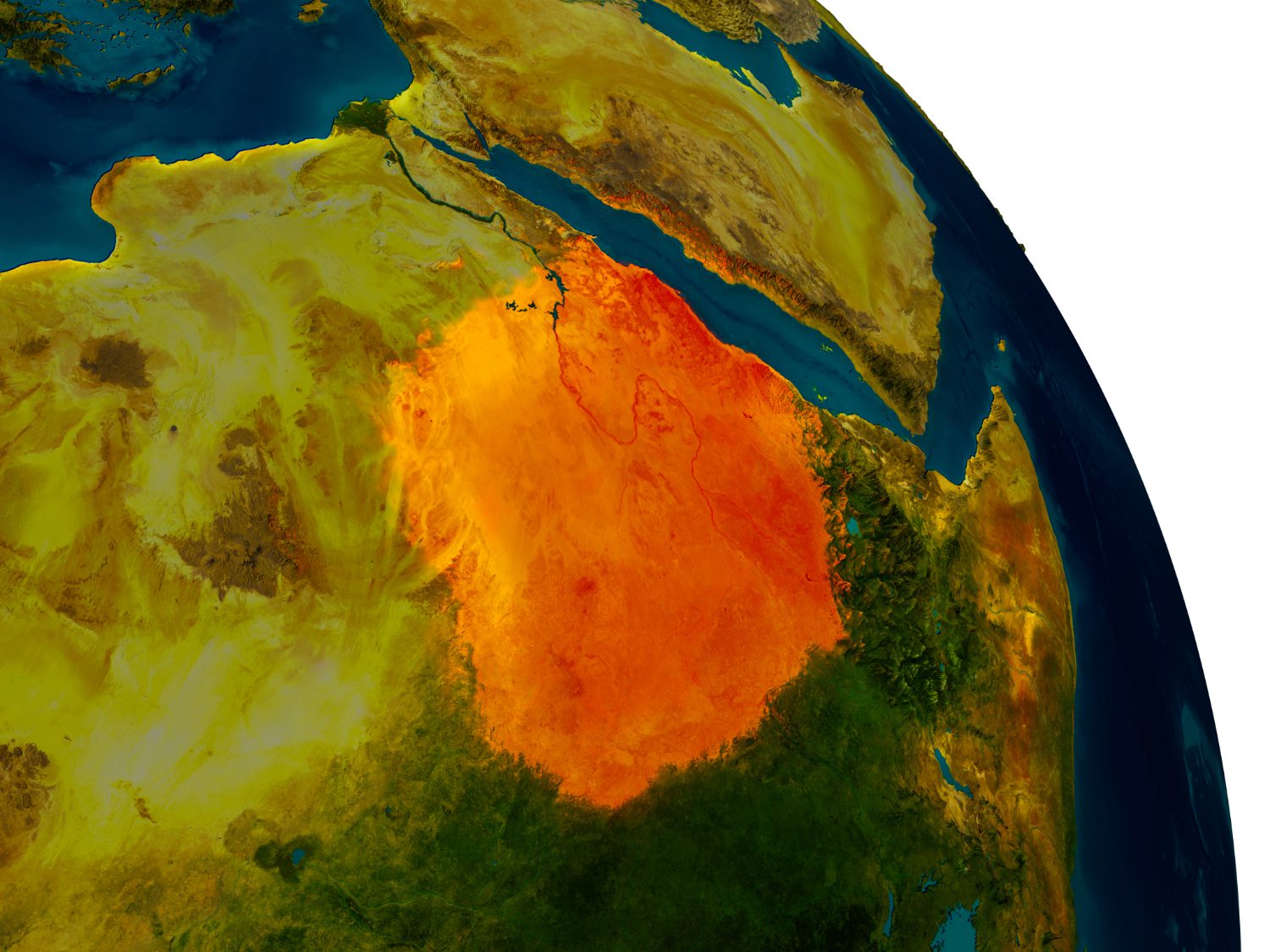

The epicenter is Israel’s war against the Palestinians in Gaza, which is reverberating across the region. The most immediate escalation is in the southern Red Sea between the United States (with Britain in tow) and the Yemeni Ansar Allah, known as the Houthis.

This inexorable escalation can only lead to a region-wide conflagration, or worse. The Red Sea is a tangle of fuses, most of them already lit.

Something bold is needed to stop the explosion. Here’s a proposal: demilitarize the Red Sea.

A pioneering United Nations peacekeeping missions was set up in 1956 to help defuse the Suez crisis. A paradigm-breaking multilateral innovation like that is needed today.

Hostilities in the Southern Red Sea

The outline story of the escalation in the southern Red Sea is this.

On November 19, claiming to act in solidarity with the Palestinians of Gaza, Yemen’s Ansar Allah (the Houthis) hijacked a ship transporting cars and announced that they would target ships associated with Israel. There were no further attacks for two weeks. (During this period there was also a seven day truce in Gaza.) On December 3, the Houthis fired missiles at three commercial ships and a US warship shot down three drones. The attacks continued. The Houthis said they were targeting Israeli ships but the attacks did not discriminate. The dangers compelled major shipping lines to reroute their ships around southern Africa, adding weeks to voyages between Asia and Europe, and adding costs to goods delivered.

The United States responded by putting together a ten-nation naval patrol called ‘Operation Prosperity Guardian.’ This was launched on December 18. Warships defended merchant ships, destroyed attack boats and shot down missiles and drones. The following day, Mohammed al-Bukhaiti, a senior Houthi official, said they would only halt their attacks if Israel’s ‘crimes in Gaza stop and food, medicines and fuel are allowed to reach its besieged population.’

On January 11, the United States and Britain launched air strikes against military sites used to attack ships in the Red Sea.

President Joe Biden’s statement read, ‘These strikes are in direct response to unprecedented Houthi attacks against international maritime vessels in the Red Sea—including the use of anti-ship ballistic missiles for the first time in history.’ That much is correct.

Biden continued, ‘The response of the international community to these reckless attacks has been united and resolute.’ That was not correct. The international community is divided. Moreover, any assumption that the US-led coalition represents the ‘rule-based international order’ cannot hold good in the shadow of the US position on Gaza. Most of the world sees the Atlanticists as picking and choosing the rules.

Bahrain is the only Arab or Muslim state to join the ‘Operation Prosperity Guardian’. Saudi Arabia, which fought the Houthis for eight long years, called for restraint and avoiding escalation. Even the Internationally Recognized Government of Yemen cannot contradict its deadly enemy on Palestine.

The Houthis resisted relentless air and ground attacks by a Saudi-led coalition for eight years, along with a blockade that reduced much of the population to starvation. In the message quoted above, Al-Bukhaiti said, ‘our military operations will not stop … no matter the sacrifices it costs us.’

On January 17, the US named the Houthis a ‘specially designated global terrorist’ organization. Humanitarian organizations were alarmed by this fearing that it might restrict their ability to provide relief. The US insists that there is a humanitarian carveout in the restrictions imposed. As airstrikes continued, the Houthis remain unbowed.

Two Narratives

Understanding this new conflict means being able to hold two dramatically different narratives in one’s head at the same time. It’s the case for Israel’s war against the Palestinians and it’s true of the conflict between the US and UK and the Houthis.

The immediate US argument is that the Houthis are endangering maritime commerce in violation of fundamental laws of the sea. The principal purpose of military action is to protect shipping from unprovoked attacks.

The broader American argument is that the Houthis are, like Hamas, ‘bad actors’ and there is little more to say about them and still fewer options for action. According to this, they are terrorists who understand only the language of force; their slogan ‘God Is the Greatest, Death to America, Death to Israel, A Curse Upon the Jews, Victory to Islam,’ says it all, and their demands are illegitimate and cannot be considered.

The Houthis insist that they are acting in solidarity with Gazans and have no intent other than ending Israel’s attacks. Yemen has a history of supporting the Palestinian cause, but it was only in November that they took any armed action in that regard. Their stance is widely popular in all parts of Yemen and across the Arab and Muslim world. They are seen, correctly, as the only entity that is providing any material leverage in support of the Palestinians.

The broader case runs like this. There must be a negotiated, political settlement to the war between Israel and the Palestinians. Israel has repeatedly violated international law and has committed war crimes in Gaza. If, in its consideration of the South African application, the International Court of Justice issues a provisional order instructing Israel to suspend military actions, or desist from certain actions, and Israel refuses to comply, this will be confirmation that Israel is unlawful.

Additionally, the Gaza war has been internationalized by the arming of Israel by the US, UK and other allies. Those great powers insist that only they have the right to blockade other countries, and others don’t. The pro-Houthi argument concludes, that like their colonial forebears in this part of the world, Israel and the US only understand the language of force.

They issued a video statement citing the Genocide Convention and concluding, ‘The Blockade Stops When the Genocide Stops.’ That’s a negotiating position.

Neither side trusts the other and neither is willing to listen to the other. But, like the war, the deafness is asymmetric. The Houthis understand the logic of commerce, not least because their potential allies are affected by it. The Houthi leader, Mohammed Ali Al-Houthi, proposed what he called ‘a simple and low-cost solution that will incur no financial expenditures for any business,’ which is that every ship passing through the Red Sea ‘should broadcast the words, “we have no relationship with Israel”.’ It’s not an acceptable proposal to the US and UK, but it shows an understanding of their position.

The US and UK show absolutely no appreciation of the gravity of the humanitarian and human rights crisis in Gaza nor the extent to which this has animated moral sentiment across the region and more widely. This is illustrated by the White House’s contemptuous dismissal of South Africa’s submission to the ICJ, as ‘meritless, counterproductive, and completely without any basis in fact whatsoever,’ and UK Defence Secretary Grant Shapps’ remarkable ignorance about well-known public statements by Israeli leaders about their intentions in Gaza.

At no point have the US or UK referred to the Houthis’ demands regarding Gaza.

A Gordian Knot of Smoldering Fuses

The confrontation between the US and the Houthis has to be seen in a regional context. Most significant is the position of Iran and its allies and proxies. One US strategic goal is to contain Iran. A particularly worrying statement by a Revolutionary Guards commander was that Iran could ‘close’ the Mediterranean if Israeli crimes in Gaza did not cease. The Red Sea airstrikes can be seen as a signal to Iran on this score.

Whether this deterrent can work is a different matter. Iran arms the Houthis but it does not control them.

Nor does America control Israel, whose stated goal of eliminating Hamas is not achievable, and whose strategic aims in Gaza are either undetermined or would be so extreme as to make a regional war inescapable. Washington gave Tel Aviv a blank check, a notorious risk factor for the unintended escalation of a limited war.

None of the parties involved, directly or indirectly, in this war are communicating with each other in a clear way. All are using force to send signals.

Add to this formula the high levels of emotion—fear, paranoia, humiliation, anger, pride, denial, revenge—and we have a barrel of explosives with many different touchpapers. Unexpected events, such as the ISIS attacks in Iran, can set off new spirals of violence.

Other players in the Red Sea are also acting recklessly.

Ethiopia is destabilizing the Horn of Africa in its attempt to get a naval base. Its surprise deal with the self-declared Republic of Somaliland for leasing a stretch of shoreline for a port, upended decades of regional diplomacy at a stroke and accelerated the arms race among the countries of the Horn.

Somaliland, for many years an island of stability, may become a contested vortex. Eritrea, recurrent destabilizer, is making new security pacts. Egypt is becoming assertive in alliance-building to surround Ethiopia.

The United Arab Emirates has been investing in ports and naval bases throughout the Gulf of Aden and beyond. The UAE has a record of backing secessionists and rogue actors, and arming them to the teeth.

Russia is active in Sudan and Libya, its plans for a naval base on Sudan’s Red Sea on pause but ready for reactivation at any moment.

Any of these actors could trigger a security crisis in the Red Sea, which could not easily be isolated from the looming Middle East regional confrontation. It’s a Gordian Knot of smoldering fuses.

Demilitarize the Red Sea

Here’s a proposed negotiated outcome: demilitarize the Red Sea.

Ending the Gaza war immediately is necessary and might soon become a legal imperative. It is a demand shared across the Arab and Islamic world, and more widely. But a solution could be found for the Red Sea should not wait.

Demilitarizing the Red Sea is long overdue. It’s a legitimate and necessary goal because the military scramble for the Red Sea is explosive from one end to the other and there’s no working diplomatic forum.

Demilitarization comes in degrees, just as a negotiated ceasefire in a war allows for permissible military activities (normally, rotation of units, supply of essentials, limited action in self-defense).

But let’s start with putting forward a bold position of total demilitarization. No warships in the Red Sea. No ships carrying arms. Once that is in place, the admirals can put their case for exceptions.

This would be inconvenient for the admirals and weapons merchants, but that is the point. Warships would have to make long detours around southern Africa.

There are only three states, plus Houthi-controlled northern Yemen, that rely solely on ports on the Red Sea. Two of them, Sudan and Eritrea, should be under arms embargoes anyway. A special carveout would be needed for the third, Jordan. Anti-piracy patrols would still be needed.

In 1956, the UN General Assembly created the UN Emergency Force for the Suez Canal, working around British and French vetoes at the UNSC. It was a pioneering model of a lightly-armed third party operating with consent to monitor a ceasefire.

The UN could set up a maritime peacekeeping force with ships from countries uninvolved in the conflicts of the region.

The geography of the Red Sea lends itself to enforcement. It would not be difficult to check ships passing the Suez Canal and the Bab al Mandab.

I expect the security commentariat to dismiss this proposal as naïve.

I argue that strategists who believe that escalation of force can achieve any good are naïve. Moreover, their naivete is well proven. Their ruinous record in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and indeed Yemen speaks for itself.

Let’s start talking about cutting this Gordian Knot and putting out the burning fuses.