We are in one of those fascinating times when our assumptions about how the world works are shifting under our feet. It’s both heady and terrifying, because so much is at stake.

In this context there’s nothing so practical as good theory. The question I pose in this blog is, what is the operating system for a world in which politics is transactional, in which those who thrive in disorder rise to the top, and in which complex institutional governing systems are reduced to the size and character of the individuals thrust into positions of power? Is it an age of disorder, a heroic age, a performance or a bazaar?

The framework we propose is the ‘political marketplace.’ It has been tested in parts of Africa and the Middle East, and it works. And over the last decade, as we have been observing it become more entrenched in the countries we study, we have seen it expand—vastly. We may now be engaged in a global experiment in a coercive political market, a.k.a. gangster kleptocracy as the norm.

As scholars and analysts, most of our contemporary theories and frameworks are indexed to recent experiences that are, in the broader scheme, anomalies—or are workable only in certain historic circumstances. For example, much political science frames its analysis around trajectories of state formation, from which it is but a small jump to the applied political economy of state building. What if Weberian-Westphalian states are a fragile and anomalous product of a certain set of factors that are no longer in play?

Many political scientists work under variants of institutionalist or neo-institutionalist economics, which assume a beneficial convergence between liberal economic theories and policies, and open-access political orders. These approaches assume that power is more effective when tamed and disciplined. There’s an alternative strand in political and economic sociology, going all the way back to Ibn Khaldun, that highlights the role of what we might call ‘wild power’—the capability of a political movement or charismatic war leader to forge a new set of rules.

Ibn Khaldun called it asabiyya, a primordial energy springing from the untutored solidarity of groups, found in its purest forms among nomads or groups at the frontiers of society, which he juxtaposed with hadhari, the civilizational force which could become over several generations, complacent and decadent. There’s an intellectual lineage here through Machiavelli to 20th century political philosophers, some of them influential in contemporary conservatism, such as Eric Voegelin, who sees the heroic spirit of American frontier democracy as a force more powerful than the constitutional formulae adapted from the European enlightenment.

When faced with disruptions, such as those unleashed by the plutocratic populist coalition in power in Washington DC, it’s tempting to look to the immediately remembered past for models. On the American, European and South Asian right, and their evocation of blood and soil nationalism and a theology of sovereign power vested in a state, there are obvious echoes with the juridical theories of Carl Schmitt, the jurist of fascism.

If Donald Trump has a vision of a garrison America, he does so while keeping intact, and weaponizing, the most important networks of global connectedness of the last quarter century, namely finance, digital communications and the reach of American weaponry. We can see a vision of global politics as an arena, or perhaps a fractal set of arenas at every level.

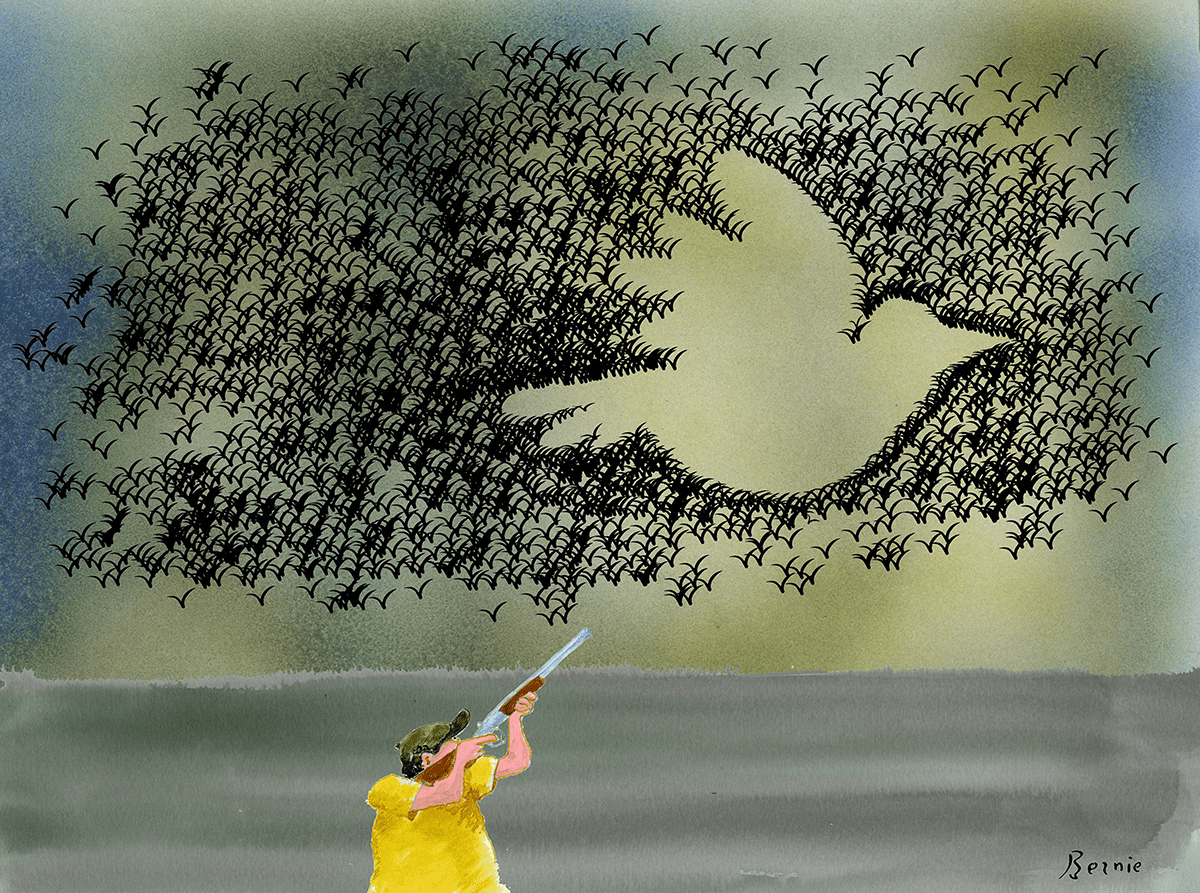

An arena is a place where people go to fight, or to contest, or as in the case of the World Wrestling Entertainment, a performative contest. It’s where the concentric circles of the audience are also stakeholders, sponsoring or betting on the contestants and enjoying that invocation of primordial affiliation and solidarity. It can be a ‘sell game’: a collusive rivalry where the outcome is decided by money, most of the time. It’s also a celebration of power and money.

What’s the operating system for politics as an arena in this sense?

We suggest it’s a combination of coercion, cash (or capital) and communication in a political marketplace. It is a market in which power—political office, political services, political loyalties, sovereignty itself—has been broken down into quanta, each of which is a tradable commodity. Power is a fictitious commodity, not created as a commodity, but treated as one. The two critical dimensions of power that are commodified are coercion and communication.

Karl Polanyi, who coined the term fictitious commodity to refer to land, labour and money, argued that the global crisis of early 20th century imperial capitalism was a contest between the logic that powered that transformative commodification, and the resistance generated by the way in which it created social wastelands. The energy of the resistance grievances was captured by fascists who cut bargains with the plutocrats themselves.

We can identify the crucial difference between then and now as the way in which power has a market value and is actively traded. This reproduces some of the same contradictions as a century ago, including the capture of grievance politics by plutocratic populists, but with this new and dominant element.

One effect of this is that political budgets—the relatively small amounts of money that are used for buying political power—have a wholly outsize influence on national economies. A political business manager (such as a country’s president) will make decisions that are perfectly rational for his political business but adverse, even calamitous, for his country’s economy.

Where the monetization of politics is most advanced is at the frontiers of contest between the driving force of political commodification—the US dollar system—and the countries resisting the US dominance of that system. For the last fifteen years, a coalition of those with deep misgivings about US hyper-dominance of the global financial system have been informally organized as the BRICS—the grouping that began as Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa and which has recently expanded to include countries in the Middle East and north-east Africa.

Over recent decades, this zone—the Red Sea Arena—has been a focal point for advanced commodification of political power. Here we can see how monetized political transactionalism functions as an operating system. In Somalia, Sudan and Yemen, the combination of weak political institutions and armed conflict drove the marketization of politics. Something similar is happening in Ethiopia and Egypt, long the exemplar of a robust deep state, is not exempt. The dominant power in the southern Red Sea Arena is the United Arab Emirates, which uses the principles of the political market in foreign relations. Particularly revealing is how the UAE treats the sovereignty of small countries, their leaders strapped for political budgets, as a commodity. With the political business managers of those countries as willing hustlers in this bazaar, the UAE is slicing, dicing and trading their sovereignty in a manner redolent of the practices of Britain’s East India Company two centuries ago.

At the time of the Arab Spring, the logic of the political marketplace framework indicated that the contest was not just between democracy and authoritarianism, but among political entrepreneurs in a suddenly-deregulated competitive market. The winners would therefore be decided by political budgets not constitutional reforms. Democracy activists resist the idea that their fate might be determined not by their claims to legitimacy but by this distasteful mercantile logic. The outcomes in Syria and Yemen unfortunately fitted this forecast, as did the fate of the Tishreen (‘October’) protests in Iraq and the Sudanese civic revolution in 2019.

The trajectory of the Ethiopian transition differs slightly. In the countries mentioned, the violence was commodified first, and communication followed. In Ethiopia it appears to be the other way around—Abiy Ahmed is conforming to the model of big man politics first of all, but the marketization of domestic politics can be expected to follow.

Nigeria is a revealing case of how a political system can operate according to this logic and nonetheless maintain a plausible imitation of democracy. It was here that Stanislas Andreski wrote, ‘The essence of kleptocracy is that the functioning of the organs of authority is determined by the mechanisms of supply and demand rather than the laws and regulations.’ That was sixty years ago. Since then, the Nigerian political elites have perfected a system of venality and gangsterism that has resisted all efforts at reform and defied recurrent predictions of its demise. Electoral politics have been crafted so as to ensure that candidates are accountable primarily to their godfathers rather than the voters. Nigeria may offer us a vision of the future of democracy in global political market.

In this series of blog posts we will explore some of the research, including methods and findings, we have been conducting on these questions over the last four years, as part of the PeaceRep consortium.