The civil war in Yemen has continued to rage in 2019, and has reduced much of the country to near-famine conditions. Next week will see the 4th anniversary of the entry into the war of the Saudi-led coalition in support of President Hadi, following the capture of the capital Sana’a by Houthi rebel forces in September 2014, forcing him into exile. According to ACLED, over 60,000 people have been killed as a direct result of the fighting between January 2016 and November 2018, including over 6,000 civilians. While a ceasefire around the crucial port of Hudeydah since December 2018 has reduced the intensity of ground fighting, the Saudi-led partial blockade of the country continues to place the country in near-famine conditions. The UN reported in February 2019 that millions of Yemenis remain “just a step away from famine”.

Despite this dire situation, arms supplies to the parties to the war have continued from arms-producing countries worldwide. However, political pressure to reduce or halt these arms sales has increased, and an increasing number of countries—albeit minor or intermediate-level suppliers to the conflict parties—have declared that they will no longer supply arms, although the precise interpretation of these commitments is sometimes uncertain.

Just over a year ago, I wrote an article, Who is arming the Yemen war? (And is anyone planning to stop?), surveying arms supplies to the conflict parties. This article updates the information with the latest available data, including the most recent edition of the SIPRI Arms Transfers Database (ATDB), released on Monday, 11 March 2019.

Who is taking part in the war?

On one side of the war are the Houthi rebel forces, or Ansar Allah. On the other, the “pro-government”, or more accurately anti-Houthi coalition, are a range of different armed forces on the ground, supported, mostly from the air but also to some extent on the ground, by the Saudi-led coalition of nations. The local forces include:

- The official forces of the government of President Hadi. According to the most recent report by the UN Security Council Panel of Experts, from January 2019, these may number around 139,000 troops, but are constrained by lack of funds, often resulting in delayed payment of wages. The official government exercises very limited authority in the “liberated” areas of the country supposedly under its control.

- The Southern Transitional Council (STC), which supports independence for southern Yemen from the north, exercises considerable power in the much of the south, and is supported and armed by the UAE. The STC frequently acts in opposition to the official pro-government forces.

- Several other militia supported by the UAE, including the Security Belt Forces (SBF), the Hadrami Elite Forces, and the Shabwani Elite Forces. The SBF are nominally under the control of the Ministry of Interior, but in practice operate outside their command, and exercise control in a number of areas. These militia have sometimes acted as allies to the STC.

- A number of other militia, often operating in particular local areas, such as the city of Taiz and on the west coast near Huydeydah, supported and funded by Saudi Arabia and/or the UAE.

The outside states participating in the Saudi-led coalition are: Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and the UAE. Morocco was part of the coalition until February 2019, when it withdrew its forces.

Other countries also play a supporting role for the coalition: in particular, the USA and UK, both of whom provide logistical support and maintenance as well as arms supplies, but also, for example, Eritrea, where UAE forces bombing Yemen have operated out of a military base at the port of Assab.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE are the major players in this coalition with influence on the ground. The UAE, in particular, has a substantial troop presence, as noted in the previous article. However, the largest number of external ground forces come from Sudan, who are reported to have had as many as 14,000 troops present at some points. However, in addition to official Sudanese military units, these forces include mercenaries recruited by Saudi Arabia, including child soldiers, according to a New York Times report.

Sudan began to provide troops to the Saudi-led war effort in 2015, in return for a $2 billion cash payment from Saudi Arabia to shore up Sudan’s ailing economy; assistance from the UAE to evade US sanctions by using Dubai as a gold-smuggling hub (Sudan being a major gold-mining country), and help in restoring the country’s status with the US, which had hitherto treated it as a pariah. However, unpaid wages and high Sudanese casualties in Yemen—Sudanese troops seem to be sent on some of the most dangerous missions—has created tensions in the relationship, with reports even of Sudanese troops turning on their Saudi and Emirati commanders.

The UAE has also recruited, armed, and trained mercenaries from around the world, in particular from Colombia and other Latin American countries.

The Houthi rebels

SIPRI has recorded in its database the probable delivery by Iran to the Houthis in 2017, of an estimated 10 Qiam-1 short-range ballistic missiles, a variant on the Scud missile, a fairly unsophisticated unguided missile. This is the only delivery to the Houthis recorded by SIPRI, in the category of “major conventional weapons”. This is in line with previous reports by the UN Security Council Panel of Experts on Yemen, cited in the previous article. Iranian supplies have also included small arms and light weapons not covered by the SIPRI database.

The most recent report by the UN Panel of Experts (PoE), from January 2019, notes that ballistic missile attacks by the Houthis on Saudi targets continued up to June 2018, but then stopped, possibly because the Houthis’ stocks of such weapons were exhausted or destroyed. However, they report that the Houthis have been continuing to use a variety of increasingly sophisticated missiles, including anti-ship cruise missiles, and UAVs. The PoE suspect that the Houthis, rather than importing complete weapons smuggled into the country (the group is subject to a UN arms embargo), they are assembling the weapons using imported components, in particular engines, guidance systems, and other key electronic components. The PoE has not been able to come to any clear conclusions about where these components are coming from, although some recovered or captured components or remnants are similar to those manufactured in China, Japan, and the USA, among others. These countries are not thought to be the direct suppliers of the components in question.

The claim that Iran has been interfering in Yemen, sponsoring the Houthis, and using them as a means of undermining their Saudi rivals, has been one of the primary justifications by Saudi Arabia and its allies for involvement in the war. Certainly, evidence of Iranian support in the form of funding, training, and arms, has been reported since at least 2014. However, many observers consider that the Iranian role has been exaggerated, taking a fairly distant supporting role at most, with the Houthis acting very much on their own agenda, rather than as an Iranian proxy. Overall, the evidence from SIPRI data, the UN panel, and other sources, appears to support the idea that, while Iranian arms supplies have not been trivial, the primary sources of arms from the Houthis has been local, from those sections of the Yemeni army that supported them, from their former pro-Saleh allies, captured weapons, and the sort of locally assembled equipment discussed above.

Yemeni government and “pro-government” forces

Since the entry of the Saudi-led coalition into the war in 2015, the UAE and the US have been the main suppliers of major conventional weapons to the pro-government/anti-Houthi side, according to SIPRI. The SIPRI ATDB reports that the US delivered one surveillance aircraft to Yemen in 2015. This follows a contract for 4 such planes placed in 2014. It is not clear at what point in the year this was delivered. Meanwhile, the UAE has delivered an estimated 145 armored vehicles of various types to government and/or other anti-Houthi forces, Saudi Arabia 25, and an unknown supplier 5. UAE is also estimated to have supplied 3 AT-802 aircraft, former crop-dusters used as trainers/light attack aircraft.

Amnesty International reported in February 2019 that the UAE was supplying a large amount of weaponry, much of it originally supplied by western countries, to a variety of militia, including some accused of war crimes and linked to Al Qaeda. This includes the armored vehicles reported in the SIPRI ATDB, as well as machine guns, mortars, and small arms, which are not included in the SIPRI database.

The Saudi-led coalition

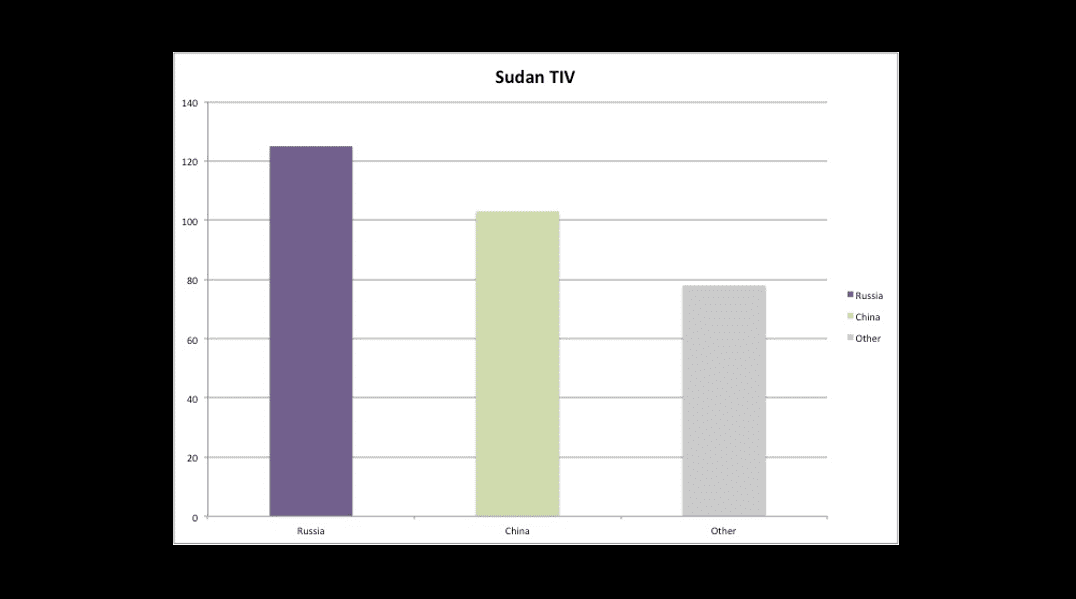

The USA remains by far the single biggest supplier of arms to most of the states in the Saudi-led coalition (see Tables and Charts, below), with the exception of Sudan, which is supplied mostly by Russia and China. The data now covers the period 2015-2017 (the previous article covered 2015-16 in most cases), with the exception of the SIPRI Trend Indicator Value (TIV) delivery data, which now covers 2015-2018. There is no sign from these figures of any slow-down in the pace of licenses, orders, and deliveries to the countries in the coalition from most of the exporters listed (Netherlands is now added to the list, as a major supplier to Jordan),indeed most suppliers have accelerated their arms trade with Saudi Arabia in particular. France has been added to the list of major suppliers to Kuwait, and Russia has joined France as a major supplier to Egypt, while Germany has also made inroads in that market. However, Italy and Sweden have made very few new deliveries and issued likewise very few new licenses to the coalition in 2017.

New orders of major conventional weapons by members of the coalition in 2017 and 2018 include:

Bahrain has ordered 16 F-16V combat aircraft from the US, along with various radar systems and engines for upgrading their existing F-16V aircraft. They have also ordered 12 combat helicopters from the US, as well as various missiles, radars, and other equipment from various suppliers.

Egypt has ordered 2 MEKO frigates from Germany for EUR1b., and 7 IRIS-T surface-to-air missile systems. Otherwise, most of the increase in the numbers in the table reflect the delivery of previously-ordered systems.

Kuwait has ordered 28 FA/18 combat aircraft from the USA, in addition to the Typhoons previously ordered from Italy. They have also ordered the latest version of the Patriot anti-ballistic missile system from the US.

Saudi Arabia has ordered 500 armored personnel carriers from France, 5 Avante-2200 frigates from Spain, along with naval guns from Italy, and is in discussions with the UK to order a further 48 Typhoon combat aircraft in addition to those previously purchased. From the US they have ordered 70 helicopters, an unknown number of batteries of the Patriot missile system, 5 naval surface-to-air missile systems, 6 Poseidon ASW aircraft, and in the biggest recent deal, 7 batteries of the Terminal High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) anti-ballistic missile system.

The UK and US have also continued to supply Saudi Arabia, which carries out the bulk of coalition air strikes in Yemen, a range of bombs and guided missiles directly for use in Yemen.

A recent report by Yemeni human rights organization Mwatana detailed 27 Saudi-led coalition strikes on civilian targets, killing over 200 civilians, where it was possible to identify the weaponry used in the strikes from recovered weapons fragments. In 25 cases, fragments were recovered from US-made weaponry, and in 5 from UK-made weaponry.

Country notes

USA: The US provides export license data for Direct Commercial Sales (DCS), but it is not possible to distinguish licenses for exports to foreign governments, and exports to US forces and government agencies operating in the destination country. Figures for deliveries include both sales through government-government Foreign Military Sales (FMS) agreements, and through DCS agreements. Figures for orders are for FMS only.

UK: The UK does not provide any information on the value of arms delivered, and provides figures for orders only on a regional basis. UK export license figures do not include ‘open’ licenses that allow for multiple shipments to one or more destinations, and which account for a large proportion of UK exports.

France: France issues export licenses to companies at the point where they begin negotiations for a potential contract. Most such negotiations do not result in actual contracts or deliveries. French license figures, which are very high, totaling tens of billions of Euros each year, therefore bear little relation to actual sales, and thus are not shown in this table.

Germany: Germany does not provide data on the value of arms delivered, except for the subcategory of “weapons of war”, for which a total figure is given, along with the total exported to EU and NATO countries, and the amount exported to the top 3 other recipients, which in 2015-2017 did not include any of the countries considered here. Figures for orders are not available.

Italy: Figures for orders are not available.

Netherlands: Figures for orders are not available.

Spain: Figures for orders are not available.

Russia: Russia does not provide any country-by-country data on its arms exports, so the only information available is from SIPRI, which collects its data independently.

China: China does not provide any data on its arms exports, so the only information available is from SIPRI, which collects its data independently.

Others includes countries with a variety of reporting practices, so that totals cannot be produced except for the SIPRI TIV, for which data is collected by SIPRI for all countries.

The murder of Saudi journalist and regime critic Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi Consulate in Turkey in October 2018, almost certainly at the orders of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), caused an international uproar, and sharpened attention on the Saudi role in the war in Yemen, and on the impact of the war on civilians–including creating famine conditions--leading to some countries rethinking their willingness to sell arms to Saudi Arabia, and in some cases to other participants in the Saudi-led coalition.

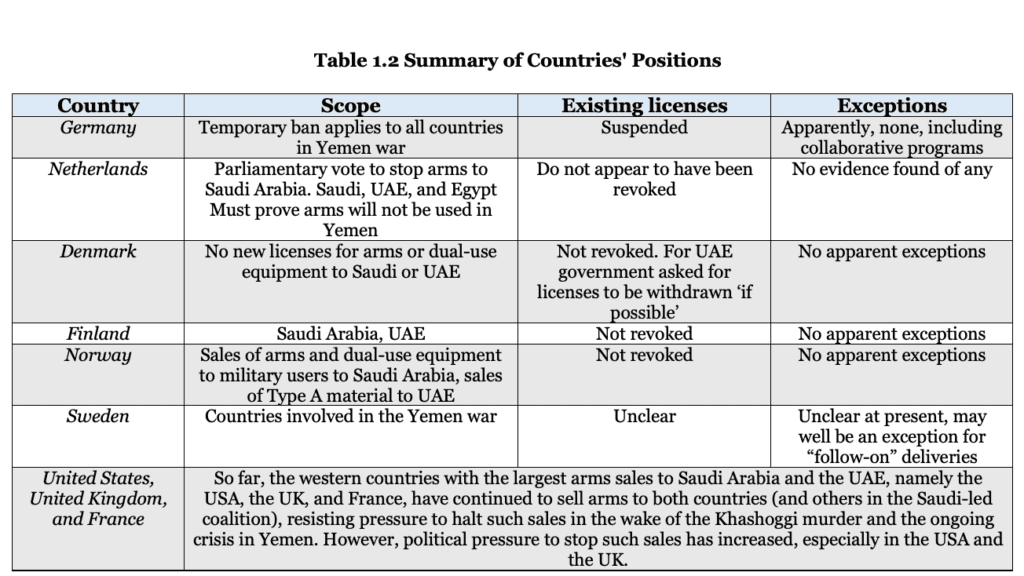

So far, Denmark, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden have all announced an intention, in one form or other, to stop selling arms to participants in the Yemen war. Even before Kashoggi’s murder, citing the high rate of civilian deaths in the conflict, Spain briefly announced a halt to the delivery of certain weapons, specifically laser-guided bombs, to Saudi Arabia in September 2018, but swiftly reversed this position for fear of losing a much larger contract for frigates.

However, the meaning of such announcements is not always completely clear, and do not necessarily mean a complete halt to all arms deliveries to the country or countries in question. A number of exceptions could potentially apply in some cases. Not all of the initial policy announcements have been followed by a clearly articulated implementation policy that would clarify these issues.

One exception could be for already approved export licenses; a government could decide to refuse all future applications for export licenses for a given destination, but allow deliveries under previously-approved export licenses to go ahead. For governments to revoke existing export licenses is quite rare, typically only happening in the case of UN or EU arms embargoes, but is certainly possible if circumstances have changed. Alternatively, licenses may be suspended until an improvement in circumstances (e.g. the war in Yemen).

A more far-reaching exception could be for existing contracts for which some, but not all, export licenses have been issued. On some contracts, deliveries may take place over a number of years. A government might decide that the desire to be seen as a ‘reliable supplier’ overrides humanitarian concerns, so that new export licenses will continue to be issued for further deliveries on contracts that were previously approved.

A related issue to this is what the Swedish export control regime refers to as “följdleveranser”, or follow-on deliveries, which include categories such as spare parts, ammunition, upgrades, and related equipment to previously supplied equipment. Under the Swedish system, there is a presumption of approval for such deliveries, unless there is an “unconditional obstacle”, such as an arms embargo, as opposed to a conditional obstacle such as the recipient’s human rights record. Similar provisions exist in the Danish and Norwegian systems. Thus, it might be possible, depending on the implementation of a new policy, even for new contracts to receive export licenses if they relate to such follow-on deliveries.

A final potential exception could relate to collaborative programs, such as the Eurofighter Typhoon. Thus, Germany might end direct arms sales to Saudi Arabia, but will they also stop the delivery of components to the UK for their sale of Typhoons to Saudi Arabia, a program in which the UK, Germany, Italy, and Spain, are collaborative partners? Stopping such sales would provide the strongest version of an arms embargo on Saudi and its coalition partners.

Germany

In fact, it appears that this is exactly what Germany has done. When Germany, in the wake of the Khashoggi murder, announced a halt to arms sales to Saudi Arabia in November 2018, there was some skepticism as to how far it would go, not least as Germany had announced similar bans on arms sales to parties to the Yemen war previously. The agreement in March 2018, for a new coalition government between Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats and the opposition Social Democrats, included a provision that no new arms sales would be approved to countries involved in the war in Yemen.

But they appeared to break this pledge in September, approving the delivery of an artillery positioning system. Indeed, according to a response by a minister to a question in parliament, Germany approved EUR416.4 million worth of export licenses for arms to Saudi Arabia between 1 January and 30 September 2018.

How this squares with the coalition agreement is not clear; one possible explanation, suggested to me by Dr. Max Mutschler of Bonn International Center for Conversion, is that these were arms that had already been awarded a production license, which is approved for potential exports before production begins. Figures are not normally provided for production licenses; only the export licenses that are approved before delivery. The coalition agreement contained a caveat that provision would be made for the ‘legitimate interests’ of the defense industry, which may have extended to approving export licenses for equipment that had previously received production licenses.

Whatever the policy was beforehand, following the Khashoggi murder it appears the Germans mean business, or rather a lack of it. As well as suspending existing export licenses, Germany has indeed stopped the supply of components and spare parts for Saudi Eurofighter Typhoons sold by the UK, through BAE Systems. This led to a dispute with the UK, but the German government rejected pleas in February 2019 from UK Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt, supported by the German arms industry, to allow such supplies. The German policy has put in doubt a planned further purchase of 48 more Typhoons by Saudi from the UK.

The temporary ban, due to expire in early March, was recently extended to the end of March [update: now until the end of September 2019], with future policy dependent on progress in Yemen peace negotiations. However, the issue is splitting the coalition government, with the Christian Democrats somewhat keener on resuming arms sales than the Social Democrats. It is not clear if this stricter interpretation on the previously-announced—and broken—pledge not to sell arms to countries involved in the war also applies to other members of the coalition.

The Netherlands

As noted in the previous article, the Netherlands was the first country to declare some form of halt to arms sales to Saudi Arabia, following a Parliamentary vote in 2016. They appear to have kept to this, at least in 2017; no arms export licenses were granted by the Netherlands to Saudi, and no arms delivered in 2017, according to the EU Annual Report for 2017. According to the Netherlands’ own annual report on export controls for 2017, two export licenses to Saudi were refused, in each case on the basis of criteria 2 of the EU Common Position on arms exports, relating to potential use of arms for internal repression.

The Netherlands did issue EUR2.6 million worth of export licenses to the UAE, and delivered EUR6.4 million, so the ban did not encompass all countries involved in the war. However, in November 2018, the Dutch International Trade Minister announced tighter restrictions on arms exports to Saudi Arabia the UAE, and Egypt, whereby these countries would have to prove that arms bought from the Netherlands would not be used in Yemen. The new restrictions also made it “virtually impossible” to supply arms to the Saudi Navy, due to its role in the blockade of Yemen.

It appears that the Dutch position does not amount to a formal arms embargo, for which an international agreement (e.g. UN or EU) would be required. However, the above evidence suggests that an informal embargo may be in place against Saudi Arabia, which may now be extended to the UAE and Egypt.

Austria

In October 2018, the Austrian Foreign Minister called for an EU-wide ban on arms sales to Saudi Arabia, stating that Austria had stopped selling military equipment to the country in March 2015. However, while Austrian arms sales to Saudi Arabia certainly dropped to very low levels, the EU Annual Report on arms exports for 2017 records around EUR1 million worth of export licenses issued by Austria for military equipment to Saudi Arabia, with EUR984 million delivered. However, this was all in the small arms and ammunition categories, so it is possible that this was for civilian use.

Wallonia

In Belgium, while the law surrounding export controls is established at a national level, the implementation of export control legislation, including decisions on export licensing, is devolved to the regional governments of Flanders, Wallonia, and Brussels region. In Wallonia, the Conseil d’Etat (State Council), an independent judicial body, suspended six export licenses for arms to Saudi Arabia, in response to a legal challenge by a coalition of NGOs. In their judgment, the judges stated that the government of Wallonia had failed to assess sufficiently carefully the potential for the equipment in question to be misused. However, while this ruling affects these individual licenses, and may have an impact on subsequent decisions, the Walloon government in October declined to enact a broader suspension of arms sales to Saudi Arabia or other coalition countries, in the wake of the Khashoggi murder.

The Nordics

Norway was the first of the Nordic states to announce a halt to arms sales to Saudi Arabia following the Khashoggi murder, on 9 November. The ban, announced by the Foreign Minister, also applied to dual use items with a military end-user, but did not however revoke existing licenses. There had previously been a ban on the export of so-called ‘Type A’ defense equipment – weapons, platforms and systems, and ammunition – to Saudi, but sales of “Type B” material – other military equipment, such as electronics, components, radars, etc., was allowed, with NOK41 million exported in 2017. Sales of Type A material to the UAE had also been halted in January 2018, but, there was no indication in the latest announcement of any further restrictions on arms sales to the UAE or other members of the coalition.

Denmark and Finland both announced a decision to stop arms sales to Saudi Arabia on November 22 2018. Denmark’s suspension of sales related only to new export licenses, with existing licenses being allowed to go through, according to the Foreign Minister. The ban, however, also included dual use goods. Denmark further announced a halt to arms sales to the United Arab Emirates in January 2019. The government also asked the police to withdraw existing export licenses, “if possible”.

Finland’s decision also halted new arms export licenses to the UAE. However, like Denmark the ban did not apply to existing export licenses. The announcement made specific reference to the acute humanitarian crisis in Yemen, rather than the Khashoggi murder.

Sweden is the biggest arms exporter among the Nordic states, and was the last to impose some form of arms sales moratorium to Saudi Arabia and the coalition. This came in January 2019, and was part of the new four-party agreement that established a new coalition government in Sweden, after four months of deadlock following the country’s inconclusive September election. The parties agreed that no new export licenses to countries involved in the Yemen war would be approved.

The scope of the Swedish decision is, however, perhaps the least clear, as there were differing views among the parties as to whether it covered the so-called follow-on deliveries discussed above. Some MPs from the largest party in the coalition, the Social Democrats, with traditional close links to arms industry trade unions, saw it is important that Sweden be seen as a “trustworthy” supplier, who would continue to ensure that previously exported systems remained functional, while their Green Party partners wanted follow-on deliveries included in the ban as well.

It was also unclear whether existing licenses would be revoked; most notably, the SEK10 million (EUR1.2 million) license for Erieye surveillance radar systems for UAE spy planes, approved in 2016, and valid for three years.

The situation in Sweden is further complicated by the fact that arms export decisions are normally made not directly by the government, but by an arms-length government agency, the Inspectorate for Strategic Products (ISP), based on the criteria decided by Parliament. However, the government can require ISP to refer license applications to certain countries to the government.

The possible exception for follow-on deliveries does not apply to the Norwegian and Danish decisions, according to the report cited above, by Swedish Television (STV).

According to a Swedish arms control expert with whom the author has communicated, the position remains unclear, with even the ISP uncertain as to what to make of the government’s position.

The United States

So far, the western countries with the largest arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, namely the USA, the UK, and France, have continued to sell arms to both countries (and others in the Saudi-led coalition), resisting pressure to halt such sales in the wake of the Khashoggi murder and the near-famine conditions Yemen. However, political pressure to stop such sales has increased, especially in the USA and the UK.

In the United States, various measures have been brought forward in one or both houses of Congress, with bipartisan support, to limit or halt arms sales to Saudi Arabia, and to reduce or end US support for the Saudi military in its execution of the war, including through a War Powers resolution, a measure whereby Congress can order a halt to the participation of US forces in a war that has not been authorized by Congress.

Most recently, on 13 March 2019, the Senate passed a War Powers Resolution ordering an end to US involvement in the war in Yemen, similar to one passed in late 2018 by the House. The Senate version will now return to the House, and if passed again, will go to the President for signing.

However, this and other measures would almost certainly receive a Presidential veto, and there are very unlikely to be enough votes in Congress to override such a veto. (The Senate measure was passed by 54 votes to 46, far short of the 2/3 majority required).

Despite the difficulties in passing legislation, Democrat Senator Robert Menendez (New Jersey), the ranking Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, has placed a ‘hold’ on the Committee’s approval of new sales of tens of thousands of precision-guided munitions to Saudi Arabia, until the Administration provides more public testimony and private information to lawmakers regarding the conduct of the war.

The UK

The UK Government has shown no signs of wanting to restrict arms sales to any country in the Saudi-led coalition. However, a House of Lords report in February 2019 concluded that the government was on the “wrong side of international humanitarian law” in approving the sale of certain arms to Saudi Arabia and other coalition members, as these weapons were highly likely to be involved in attacks on civilians. This report carries no legal force, but may well add weight to the forthcoming appeal by UK NGO Campaign Against Arms Trade, seeking to overturn a lower court verdict that found that the government had not acted illegally in approving arms sales to Saudi Arabia. The appeal is to be heard in mid-April 2019.

France

In France, President Emmanuel Macron has strongly defended French arms sales to the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia. Indeed, he attacked German Chancellor Angela Merkel for what he called “pure demagogy” in halting arms sales to Saudi Arabia, saying that such sales had nothing to do with the Khashoggi affair. While there has been some media debate in France over arms sales to Saudi, there does not seem to have been significant political pressure on the French government to change course.

The murder of Jamal Khashoggi and threat of mass civilian starvation in Yemen have thus created a tougher political climate for countries selling arms to Saudi Arabia and other members of the coalition. However, while a number of countries have stopped some or all arms sales to Saudi, and in some cases other coalition members, these are mostly relatively small exporters, with the exception of Germany. However, while Germany is a major arms exporter overall, it has not been one of the primary suppliers to the countries concerned. The largest western sellers have not yet changed their policies, but political pressure against arms sales to Saudi is increasing, especially in the US, where the independence of the legislature from the executive (unlike in the UK and France) has allowed Congress to become a focus of opposition to arms sales.

Nonetheless, opposition parties in the UK are opposed to arms sales to Saudi Arabia, and the moves by allied nations might make such a position considerably easier, politically speaking, to implement, were there to be a change of government. A further sign of the increased pressure on the UK has been the much greater efforts shown by the UK government, in particular Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt, in seeking to push forward peace negotiations in Yemen—while the government has no intention of stopping arms sales to Saudi Arabia, it is showing more urgency in seeking to defuse the main source of controversy around these sales, namely the war in Yemen.